Factoring Time in Architecture in the Cairo Trilogy: What lies between Tradition and Modernity

- Taher Abdel-Ghani

- Jul 3, 2023

- 6 min read

Filmmaker Hassan Al-Imam's trilogy’s architectural imagery embodies an intertwined connection between the visual language of space and the socio-spatial narratives that compose the local setting. Through the examination of such connection within the settings across the three films, the article reveals the influence of non-physical elements on the physicality of architectural and urban space, creating a visual narrative from social collectivism to individualist fragmentation.

Filmmaking in the Middle East erupts critical debate on the social aspect of space and its foregrounded role in the cinematic narrative timeline. As a dynamic visual tool, Arab filmmakers have always used spatial elements, whether abstract or concrete features, to put forward contemporary forms of identity and representational attributes of social organization.

Hassan Al-Imam’s Cairo Trilogy, Bayn Al-Qasrayn [Palace Walk] (1964), Qasr Al-Shuuq [Palace of Desire] (1967), and Al-Sukariyya [Sugar Street] (1973), which are based on the novels by Nobel Prize laureate Naguib Mahfouz, is a vivid depiction of old values and the new political and intellectual trends in modern Egypt. It follows the life of an Egyptian family in several districts of Old Cairo, tracing their aspirations and agonies, paralleled with their struggle against the British occupation from 1917 till 1944.

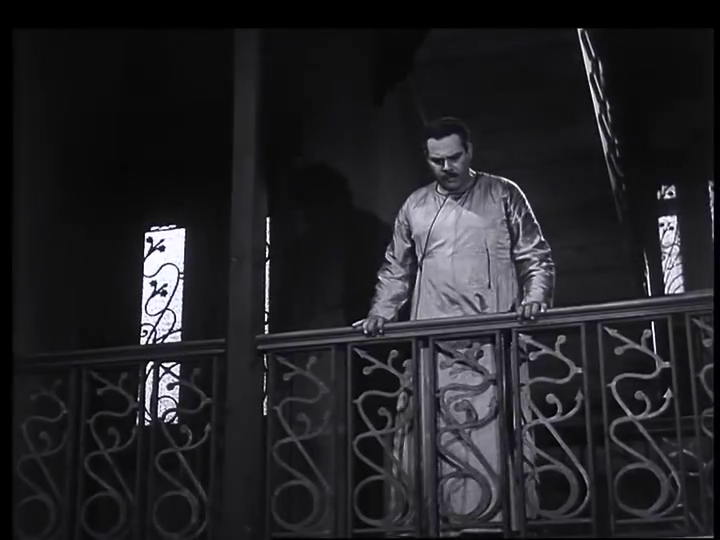

The trilogy opens with the Jawad’s family living in a traditional two-story house, headed by Cairene patriarch Al-Sayed [Mr.] Ahmed Abdel-Jawad, his wife Amina, the family matriarch and the obedient woman, his three sons – the dissolute hedonist Yasin, the patriotic and idealistic Fahmy, and the soul-searching intellectual Kamal, in addition to his two daughters – Khadija and Aisha, whose roles are limited to caring for their father and helping with the household chores.

As the events unfold throughout the three films, second and third generations appear and are scattered across different housing clusters revealing the changing nature of socio-spatial characteristics of 20th century Cairo.

The Trilogy's Illustration of Time and Space

The Cairo Trilogy’s portrayal of domestic space illustrated a temporal shift from living within collective communities to dwelling across a spread individualist society resulting from the fast-paced industrial city. Not only family members were actively progressing throughout this shift, but also architectural elements shaping the newly-born domestic space were dominant key themes explored.

The notion of time embodied an architectural entity foreshadowing the emotional distances that have pursued the characters. The ruling theme in this section is one of representation and its challenges. How did the films represent such conflict? How was the filmmaker able to meet this challenge?

The three films displayed a cross-cutting relationship between tradition and modernity, each embodying one another. The trilogy spanned across a gradual superimposition of modernity over tradition on one hand while emphasizing features of tradition within the agonies of modernity on the other.

Filmmaker Hassan Al-Imam’s adherence to anachronistic tradition can be argued as a retrogressive past that adds value to modern times. On a certain scale, this approach maintains the importance of self-identity of culture within the context of time and place.

The Architectural Features of Socio-Spatial Transformation

Film proposes symbolic spatial aspects whose images, composed of metaphorical signs and symbols, are observed and interpreted by the public, and, in response, compose new meanings and typologies. The Cairo trilogy displays several key themes explored through the architectural elements employed throughout the narrative that reflect the realistic accompanying image of the city at the time.

The use of indoor spaces juxtaposed with the spatial organization of the furniture depicted the modern built environment that, throughout the three films, questioned the very commitment of the characters to the traditions of the household. Additionally, it revealed social perceptions concerning the characters’ behavior, intentions, and beliefs.

This section explores three features of architectural spatial transformations that foreground the underlying description of modern society shifting from collectivism to individualism, 1) the gradual decline of the role of the rooftop, 2) the shift from multi-story households to different clustered single-story ones, and 3) the architectural division of domestic spaces that have challenged traditional organization.

"Is representation ever generous, complete, or dignified? Perhaps having power over representations does not have to be our goal. Why not aim to have the power to negotiate and inhabit them with a certain measure of ambivalence? To meditate on the very fibers threads, and stitches that hold our images together? To live in them and reanimate them via our own subjectivities?" - W.J.T. MITCHELL

1) The Gradual Decline of the Role of the Rooftop

The rooftop appears in the first two films, Palace Walk and Palace of Desire, as two different characters going through a dramatic sociological shift from the traditional revolutionary value to the embodiment of individual desires and metropolitan fragmentation.

Fahmy’s character sets an underlying theme of a quasi-fragmented modern city in conflict with domestic values. He uses the rooftop as a shelter for self-expression of patriotism and revolutionary thoughts, whilst at the same time, a romantic escape to meet Maryam.

As the story unfolds with the death of the Egyptian revolutionary Saad Zaghloul, features of social depression and frustration gradually arise in Palace of Desire, as Fahmy’s brothers, Kamal and Yassin, are faced with political and social unrest. This has resulted in the breakdown of the Jawads’ family in the third film, Sugar Street, as quasi-fateful events of love and seduction transformed the characters into pitiable victims. Individual happiness stood on one side, while family and tradition stood on the other.

2) From the Multi-Storey House to Clustered Single-Storey Households

The transition from the traditional collective house to individualistic single-story households marked the appearance of several political ideologies in Egypt. In Palace Walk, the household, which is the traditional well-known Bayt Al-Suhaimi, expressed collective values through its architectural elements, e.g. massive chambers, high ceilings, elongated mashrabiyyas, arched rooms, and latticed windows.

These elements spotlighted the patriarchal figure, El-Sayed Ahmed Abdel-Jawad, as the strict character of Old Cairo setting rules of Muslim piety and sobriety. His authority leaves no space for his wife and children to question his personal life beyond the household.

As the story progresses, and the Jawad family expands to the second and third generations, we enter several households that embody modern spatial elements. These clusters represented the repercussions of Ismail Pasha’s European ideals of planning that started in the late 19th century that forced many of the elite families to relocate to the newly established Europeanized quarters of the city.

Hence, social aspects of individualism and modern desires became vivid in Sugar Street through Abdel-Jawad’s three grandsons: Ahmed Shawkat, a college student and socialist, his brother Abdel-Moneim Shawkat the secularist, and Radwan Yasin, a nationalist opportunist whose loyalty to the state is unquestionable.

Reflecting such fragmentation in the modern house, the architectural organization no longer defines certain domestic boundaries, but it has provided more space for civic expression. The once central patriarchal figure imposing himself at the dining table in Palace Walk is no longer the authoritative charismatic person in Sugar Street, where every family member eats at the dinner table without gender hierarchy.

3) The Gradual Distinction of Domestic Spaces

The trilogy treats separation and its social consequences through Kamal Abdel-Jawad, the youngest sibling of the Jawad family whose story highlights the transition of the city’s character towards self-discovery. Kamal’s coming-of-age story is an existential journey that comes to terms with uncertainty and modern rebirth.

His confined thoughts and newly-born ideologies are portrayed spatially within his room separate from the rest of the household spaces in Sugar Street. It is a private domain that encloses his desires and interests in a distant proximity from the modernistic social trending values.

Kamal’s desires illustrate the spatial fragmentation of the Jawad family, which completely contrasts the behavior at the beginning of the story.

In one scene in Palace Walk, Fahmy escorts a local physician to Amina who lies in her bed with an injured leg. The living space seems to blend within the adjacent spaces, which mainly function as dining, and sometimes, sleeping spaces.

Contrasting with such order are the same spaces in the new Jawad household, where there is a clear distinction between the living, dining, and sleeping spaces – a dominant feature of modern residences.

In this sense, the melodramatic fabric of the trilogy can be translated spatially into physical objects that convey connotations of the present greater than its relationship with the past. Buildings and spaces are seen as mnemonic manifestations of collective memory, and so resemble a unique social context whose history is embedded within contemporary everyday practice.

Have you seen The Cairo Trilogy yet? Have you read the novels? Do you think there is more to the films than what is mentioned? Please share your comments, ideas, thoughts, criticism, and/or any sort of information and/or interesting facts.

Comments